On the fifth of January, a global tide of heartfelt condolences washed onto Lusitanian shores, lamenting the death of Benfica legend Eusébio. Old Trafford, Anfield, the Santiago Bernabeu, all paid their respects with a minute’s mourning prior to kickoff. It was a tragic bit of news that genuinely gripped the wider footballing community.

But only a few hours after Eusébio’s passing, fate exercised its twisted nature and Mustapha Zitouni, another African great, left our world. Though the two were seemingly unattached, their tales did follow a similar path before forking at a critical juncture: both were born in colonized African nations, both left their native countries to play professional football abroad, and both were among the best players in the world at their position.

Though Eusébio excelled by playing for colonial Portugal, Mustapha Zitouni gave up the French national team and its spotlight, preferring to tilt it instead onto a cause much larger than himself: the Algerian independence movement.

The comparison is, by no means, a slight on the undeserving Eusébio. Such a formulation would be unfair as Eusébio is not Zitouni: they did not face the same political, social, and personal contexts. Contrasting their respective fates is merely a manner of highlighting the magnitude of Zitouni’s sacrifice.

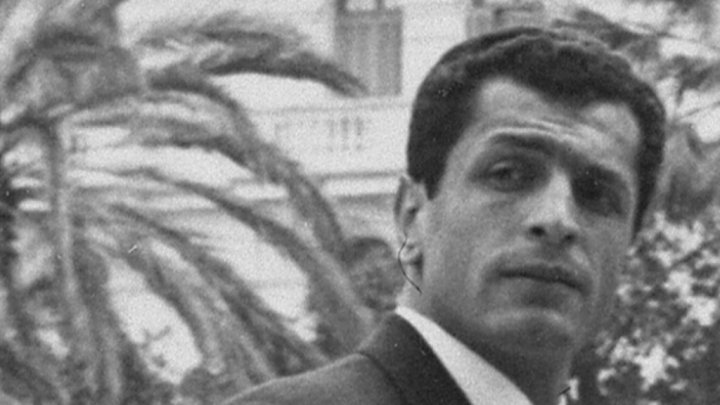

The player

Mustapha Zitouni was born in the popular district of Bologhine in Algiers. He was somewhat of a late bloomer, only signing his first professional with Cannes at the age of 25. One year in the top flight was enough to convince Monaco, who wasted no time in purchasing the graceful libero, signing the Algiers native to a long-term contract. And it would be there that Mustapha Zitouni would make a name for himself in the métropole.

In 1958, Zitouni was approaching the pinnacle of his career. Monaco were chasing league leaders Stade de Reims in the French championnat, and had also advanced to the semi-finals of the Coupe de France. The Algerian colossus had so impressed for the principality that he soon became a full-fledged international.

Though he only made four appearances for Les Bleus, it was in the international arena that Zitouni managed to imprint his name in French folklore. Group 2 of UEFA’s 1958 World Cup Qualification was shaping up to be a two-horse race between France and Belgium. The final match of the group saw France travel to Heysel, where only a win was needed to qualify the Red Devils of Belgium.

With the match stuck at a precarious stalemate, Paul Vandenberg, Belgium’s leading goal scorer during the qualification campaign, broke through the French rearguard and toe-poked a shot under the body of a diving Claude Abbes. As the ball seemingly trickled into an empty net, Zitouni stole in and booted the lopsided leather off of the goal-line. His valiant clearance made headlines the next morning in the French tabloids as his heroics had ensured that France would be travelling to Sweden in the summer.

And Zitouni was no one-match wonder. He put together equally impressive showings against Hungary, and England, though it was maybe in his fourth and final international appearance that he turned in his most memorable performance. The match took place in March of 1958, as Spain visited the Parc Des Princes for an international friendly. Zitouni did not put a foot wrong, marking the incumbent Ballon D’Or winner Alfredi Di Stefano out of the match. Di Stefano’s club president – the shrewd Santiago Bernabeu – was in attendance that evening and was so impressed with France’s #5 that he sought to cajole Zitouni into a potential move to Real Madrid.

But Zitouni would not be joining Real Madrid, and he would not be joining his international teammates in Sweden for the World Cup in the summer, for he had already given his word to leave France and join the Front de Liberation National (FLN) team. Twelve other Algerians plying their trade in the championnat would accompany him in defecting as they left their glamorous livelihoods for bumpy dirt pitches in Tunisia.

Zitouni spent the next four years – the prime of his career – travelling the Middle East, the Eastern Bloc, and Southeast Asia in an effort to raise international sympathy for the Algerian independence movement.

He maintained constant correspondence with his friends in the French national team throughout his travels. Raymond Kopa, in particular, exchanged a series of letters with Zitouni expressing sympathy, courage, and regret for the status quo.

Indeed, there are indications that the ramifications of Zitouni’s absence may have been more than sentimental. France would advance to the semi-finals before being dismantled 2-5 by a precocious Pele and his Brazil. In the 36th minute, Raymond Jonquet, who was Zitouni’s replacement, broke his fibula and was forced to hobble on one leg for the remainder of the match. At the time substitutions were not permitted, and France practically played with ten men for the rest of the encounter.

Of course these theoretical suppositions do not guarantee a change of fortunes for Les Bleus. But such musings are only natural when you ponder that France were missing four FLN players (Brahimi, Ben Tifour, Mekhloufi, Zitouni) who were all regulars during the 1958 qualification campaign. What is certain is that Zitouni and his compatriots turned down the opportunity to shoot for the very apotheosis of celebrity in forsaking the World Cup and all of its attractive offerings.

Appropriate farewell

On the sixth of January, tens of thousands crammed into Estádio da Luz as Eusébio’s coffin was showered with hymns, scarves, and adoration. His feats on the world stage were extolled in broadsheet newspaper obituaries and the multitudes grieved. A few days later, Mustapha Zitouni was buried in Nice’s Cimétiere de l’Est. His was a quiet, solemn ceremony for family and close friends. In life, and in death, Mustapha Zitouni never collected the fame and fortune he was due.

In a consolatory letter to the Algerian Football Federation, Sepp Blatter wrote, ‘All who watched him remember Zitouni as one of the best central defenders of his era.’

But, with all due respect, the president of FIFA missed the point. Those who remember Zitouni will not only remember him as one of the best central defenders of his era. No, that would be a gross injustice. Those who remember Zitouni will remember him as a free man. Primarily a man of principle, and only then, a man of spectacle. His legacy is one of sacrifice, strength, and bravery. It’s an immortal legacy that time, fame, or fortune can never adulterate.